Carl Beam: The New World

Gallery Gevik is pleased to present Carl Beam: The New World, a retrospective exhibition and the first in a commercial Toronto gallery in many years. Of Ojibwe heritage, Carl Migwans Beam (1943-2005) has exerted a strong influence on generations of Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists. His work survives as a milestone in the development of a unique and powerful voice within the context of the presence of Canada on the international art scene. This exhibition consists of five landmark works by Beam, incorporating signature imagery and techniques, as well as several works on plexiglass, ceramics and etchings, providing an unparalleled opportunity for collectors to own rare works that are almost now only found in museum collections. We’d like to extend special thanks to Anong Migwans Beam for her guidance and Virginia Eichhorn, Executive Director of Quest Art School and Gallery and former Chief Curator of the Tom Thomson Art Gallery for her illuminating curatorial essay.

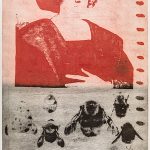

Various Ways to Travel in North America, 1990

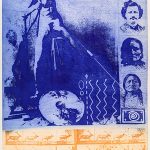

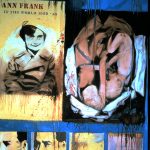

Self Portrait as John Wayne, Probably, 1990

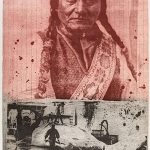

Carl Beam was born in M’Chigeeng (West Bay) on Manitoulin Island. As a child he was sent to the Garnier Residential School in Spanish, an experience referenced in several works through inclusion of a class photo in which he outlined himself with red ink. Beam’s art studies were at the Kootenay School of Art, the University of Victoria and the University of Alberta. In 1986, the National Gallery of Canada was the first of the major Canadian galleries to recognize Beam’s work with the purchase of The North American Iceberg, the first work acquired from an Indigenous artist as a contemporary work of art rather than as an ethnographic piece. From 1983-1992 his work was included in all the landmark exhibitions that altered the segregation of Indigenous art in Canada.

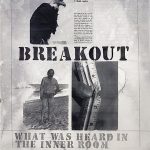

Beam told stories with pictures. His works can be read as morality plays juxtaposing long held perceptions with challenging alternatives. His well-known images, a Pieta, an embryo, Abraham Lincoln, Sitting Bull, a crow, the Pinta and Maria, Einstein, along with images from his family history, were used as cultural markers overlaid with references to time and space. With a linear pattern or formal grid, he tried to visually create the fourth dimension in his work, a spiritual space inhabited by a defiant intellect. That he was an artist of Indigenous and settler heritage added to the scope of the complex subjects he chose. Through his provocative and unrelenting imagery, Beam grappled with some of life’s most difficult issues: questions of identity, prejudice, homelessness, hunger – and how do we choose to live a “good” life. For Beam, these issues were never isolated. Our everyday actions and decisions have profound implications and effects on the world we live in. Thus, his art, and his life, became challenges to the prevailing status quo, and rallying cries and exhortations that we CAN do better if we try.

Although he had formal art training, Beam also had a number of life experiences not specifically related to art-making. He culled images from his own life experience and frequently juxtaposed them with historical and contemporary images, thus relating the “personal” with the larger “societal” picture. Stylistically his technique is more connected to Rauschenberg than to the Woodlands or traditional Indigenous art styles. His innovative techniques, in fact, have been emulated by a new generation of artists – Indigenous and not. Drawing inspiration from Anasazi and Mimbres cultures and techniques, Beam combined these with his own signature techniques creating a unique approach to ceramics as a means of contemporary art-making. In an artist statement in 2005 Beam wrote: “The hemispherical quality of a large bowl still excites me … it is a universe unto itself, where anything can happen – the designs are limitless.”

Carl Beam’s paintings, etchings and constructions stand at the cutting edge of contemporary art and push insistently at its boundaries. In the 1990s Beam completed a self-portrait. It consisted of an image of a feather. His family’s Ojibwe name is Migwans which means “bird” or “feather”. Beneath the solitary feather he wrote: Carl Absolutely Nothing Migwans – a reference to the fact that the name “Beam” was an assigned one, with which there was no real connection. But in that he may have been incorrect. While it was not his family’s traditional name, “beam” can mean many things: something that provides support; something that shines brightly and illuminates things; a means of transmission for energy or information. In that, “Beam” is a fitting moniker. For he did all those things throughout his life. As an artist, and as a man.