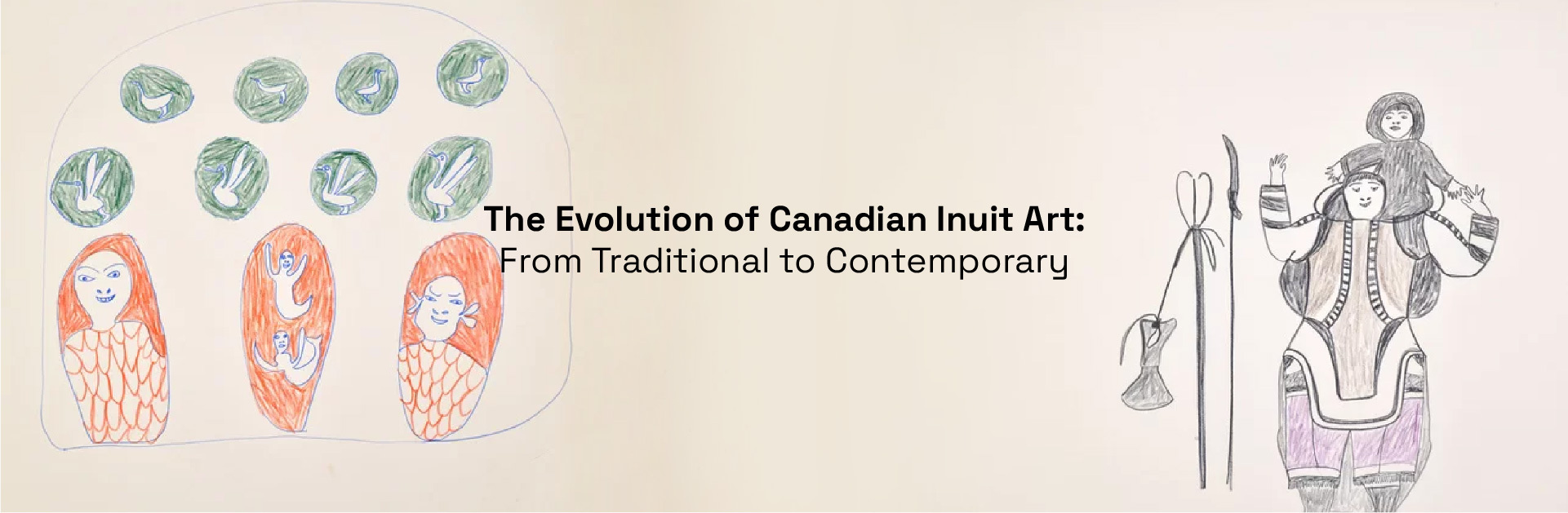

The Evolution of Canadian Inuit Art: From Traditional to Contemporary

Beautiful paintings and sculptures are not the only works of Canadian Inuit art. It provides a glimpse into a multifaceted cultural heritage. To properly value this creative heritage, we must dispel the myth that there is just one “Inuit art style.” The truth is much more intriguing, showing a dynamic mosaic of artistic expressions and civilizations that have changed throughout time.

The rich history of Canadian Inuit art is intricately entwined with the Inuit people’s relationship to the harsh Arctic environment. From utilitarian implements to spiritual artifacts throughout the ages, artistic expression has developed into globally acclaimed modern art. Let’s take a historical tour to see the amazing evolution of Inuit art.

What is Inuit Art?

The term “Inuit art” refers to a wide variety of artistic works produced by the artists – Inuit people of Canada (Indigenous people from the Arctic regions of Canada), including anything from drawings and sculptures to textiles and digital art. While Alaskan Inuit identify as “Yupik” and Greenlanders call themselves “Kalaallit,” the name “Inuit” itself is a relatively new one in Canada. Despite these differences, there are clear parallels between their artistic disciplines that allude to a common heritage and cross-cultural interactions. Here’s a glimpse into some of the major periods:

1. Pre-Dorset (4,500 years ago – 1,000 BC)

Even though there aren’t many artifacts from this era still in existence, the finely constructed tools and weapons that have been found demonstrate a strong aesthetic sense. Inuit carvings were useful objects with exquisite ornamentation added. Though essentially utilitarian, these tools represent a “hunting magic” that would permeate the following cultures. As whalers from the United States and Europe started to visit traditional hunting grounds, these artifacts became a source of income. These so-called “trade sculptures” included animals important to the Inuit way of life, such as birds, whales, polar bears, seals, and others. Materials include marine ivory, whalebone, antlers, and various natural stones.

2. Dorset Culture (700 BC – 1000 CE)

Some of the oldest pieces of Inuit art were created by the Dorset people, who are thought to be the first Indigenous Canadian Arctic culture. Their work seems to have magical-religious meaning, with a major emphasis on tiny sculptures made of ivory, bone, and antler. Bear and falcon sculptures, which frequently have skeletal patterns, might have been a part of shamanic ceremonies.

3. Thule Culture (1000 CE – 1700 CE)

The modern Inuit descended from the Thule people, who left Alaska and carried with them a skilled tool-making legacy. With their arrival, Dorset art essentially disappeared, but early Thule carvings still display some artistic influences.

4. Historic Period (1700 CE – Mid-20th Century)

Inuit art changed during this time due to contact with European explorers. Trade products with smaller, more detailed carvings of hunting scenes and animals gained popularity. Larger, more detailed sculptures were made possible by the widespread use of soapstone.

5. Contemporary Period (Mid-20th Century – Present)

The current Inuit art scene is a colourful, creative eruption. Although carving is still significant, artists are using a greater variety of media and subjects. Contemporary Inuit art addresses social issues, environmental concerns, and the changing Inuit identity in a globalized world. It takes many forms, from vivid paintings and detailed prints to digital art and textiles. The openness of Arctic communities to greater artistic output and accessibility to a willing worldwide market can be reflected in a modern type of Inuit sculpture.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the Canadian government and various art organizations actively encouraged Inuit communities to produce art for commercial purposes. This period witnessed the establishment of cooperative movements, such as the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative in Cape Dorset, which played a crucial role in promoting Inuit art globally.

Prominent Inuit Art Communities and Their Artists

One of the most prominent supporters of Inuit art is Phillip Gevik, director of Gallery Gevik. Since 1976, Gallery Gevik has exhibited First Nations and Inuit art, amassing an outstanding collection of graphics and sculptures. The gallery features an extensive collection of Indigenous art, including sculptures, graphics, and drawings in a variety of styles and subjects. They carry Inuit prints from Cape Dorset, Baker Lake, Pangnirtung, Povungnituk, Holman Island, Kangiqsualujjuaq and more, sharing an equal passion for original Inuit drawings.

Cape Dorset

Known as the “Capital of Inuit Art,” Cape Dorset is a little town in Nunavut, Canada, on Dorset Island. This far-flung Arctic village is well known across the world for its outstanding contributions to Inuit art, especially in the fields of printmaking and sculpture. The distinctive creative legacy of the town is well ingrained in the Inuit people’s natural environment and cultural customs.

A well-known advocate for Inuit art, Gallery Gevik features a large collection of pieces from Cape Dorset. The collection showcases impressive Inuit sculptures, such as:

- Sedna: A captivating sculpture depicting the sea goddess of Inuit mythology.

- Smoking the Pipe: An intricate carving illustrating traditional Inuit practices.

- Drummer: A dynamic sculpture capturing the essence of Inuit musical traditions.

The painters’ identities are still a mystery because these sculptures date back before history was written.

Apart from these exquisite sculptures, Gallery Gevik has a wide selection of Inuit prints created by artists from Cape Dorset. Among the notable prints are:

- Napachie Pootoogook: A series of prints by the esteemed artist Napachie Pootoogook, showcasing her unique perspective and artistic vision.

- Meelia Kelly: Prints by Meelia Kelly reflect the rich cultural heritage and natural beauty of the Arctic.

- Pudlo Pudlat: An innovative artist from Ilupirlik near Amadjuak, NU, later based in Kinngait (Cape Dorset), NU, is celebrated for his unique works that blend traditional Inuit lifestyles with modern technology, earning him a retrospective at the National Gallery of Canada and inclusion in major collections and exhibitions worldwide.

Baker Lake

Baker Lake is renowned for its vivid and striking illustrations and prints. Shamanistic customs and regional mythology are popular sources of inspiration for the region’s painters, who produce profoundly spiritual and visually arresting works of art.

Gevik Gallery features many Canadian Inuit art prints by famous artists from Baker Lake, including:

Povungnituk

Povungnituk, located in Nunavik, Quebec, has a distinctive carving tradition. The community’s artists are known for their narrative sculptures, often depicting scenes from Inuit legends and daily life. The use of local stones, such as soapstone and serpentine, gives Povungnituk carvings their unique texture and aesthetic.

Holman Island

The printing of Holman Island, now called Ulukhaktok, is well renowned. Since its founding in 1961, the Holman Eskimo Co-operative has helped regional artists create a variety of prints. Holman Island’s artists are renowned for their vibrant and intricate compositions that perfectly capture the spirit of Arctic life.

Kangiqsualujjuaq

Kangiqsualujjuaq, though lesser known, contributes significantly to the diversity of Inuit art. The artists from this region often focus on themes of nature and wildlife, using both traditional and contemporary techniques to create their works. In Gallery Gevik you can find works of:

- Tivi Etok

- Kullutu Pilurtuut

Inuit art is a dynamic representation of the resilience of the human spirit. It is a tale that has been painted on canvases, carved into stones, and woven into fabrics. Let us keep in mind that we are doing more than merely appreciating exquisite things as we delve further into this rich artistic history. We are establishing a connection with a history, a culture, and a dynamic modern voice that continues to influence the environment we live in.

Leave a reply