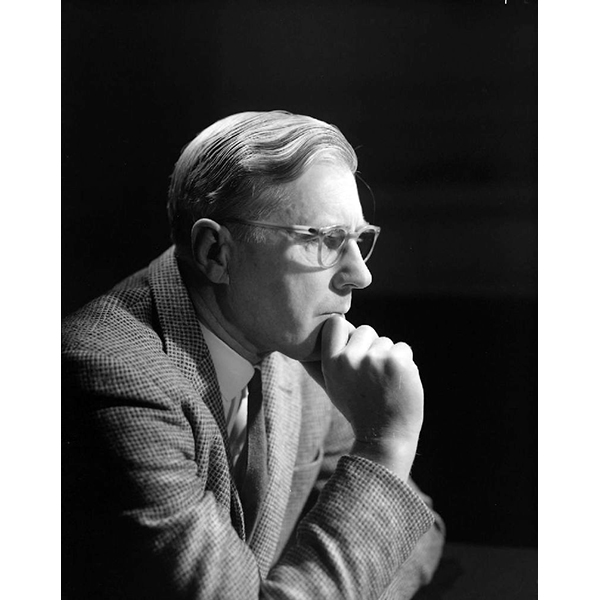

Goodridge Roberts

Goodridge Roberts (1904-1974) - Artist Biography

Goodridge Roberts trained at the École des beaux-arts de Montréal from 1923 to 1925 and, through the support of his aunt, the New York editor and art critic Mary Fanton Roberts, enrolled at the Art Students League in New York from 1926 to 1928. Taking courses with American painter and founder of the Ashcan School, John Sloan, he began a lifelong commitment to modernism. Moving to Ottawa in 1930, Roberts held his first professional solo exhibition, an annual event that would continue until the late 1960s. He then became the first resident artist sponsored by the Carnegie Corporation at Queen's University (1933–36). Afterwards, he moved to Montréal, where he would remain for most of his life and began regular participation in local and national exhibitions, a pattern he would follow throughout his long career. In 1937, his work had its first international showing in London, followed by his frequent appearance in group exhibitions of Canadian art in the United States and Europe. A year later, he joined John Lyman’s short-lived Eastern Group. In 1939, he became a founding member of Lyman’s Contemporary Arts Society.

Along with his watercolours, Roberts showed works on canvas, particularly self-portraits and images of his first wife Marian, who would be the subject of numerous nude and clothed figure paintings. He also produced images of his young cousins, reflecting a particularly Montréal interest in paintings of children. Intertwining remoteness and immediacy in his self-contained, almost stark images of the body would remain a constant throughout his career, regardless of the identity of the sitter or model.

At the same time that he painted the placid Québec landscape, he continued his interest in the city, particularly through late-afternoon images of the simplified facades of dignified buildings in Old Montréal. Still-life imagery also became an important theme because, unlike pictures of people or places, Roberts had complete control over the choice and arrangement of the individual elements while still assuring the motif’s objective sense of authenticity. At this time, he also began a lengthy tenure at the Art Association of Montreal's School of Art and Design between 1940 and 1949 and again in 1952, except for service as a war artist from 1943 to 1945. Roberts’s most valuable teaching skill was as a role model and his dedication to his painting became the major influence on his many students, including Jacques de Tonnancour (who would publish the first monograph on Roberts in 1944), John Fox and Paterson Ewen. Decades later and because of the attention paid to his work by the American critic Clement Greenberg, Roberts’s painting would engage a younger generation of Canadian artists, especially in the Prairies.

By the early 1950s, Goodridge Roberts had gained national prominence through his regular participation in numerous Canadian and international exhibitions as well as his extensive positive reception in the English and French Montréal press and Canadian magazines. While the Laurentians and then Québec’s Eastern Townships (as well as Montréal’s Mount Royal) had provided the tranquil settings of most of his landscape images, Roberts now began to paint the more rugged north shore of the St. Lawrence, the scraggly terrain of southwestern Québec and the dramatically austere Georgian Bay. Because of his second-wife Joan’s ties to Ontario, Roberts would return almost annually, painting a series of landscapes that impose his own personality on this overly familiar site. These changes in venue and topography prompted more energetic brushwork, less contained shapes and a reinvented composition with greater emphasis on the sky to shape the pictorial space. As well, his still-life pictures were often replaced by interior images where the room itself describes the same truth to observation as the objects displayed on a table. The most experimental of his paintings from the later 1950s, the interiors would continue to function as a form of self-portraiture as the subject represents the place where he painted and the things he possessed. He also produced series of monumental nudes, where the gestural scrutiny of the posed body and the direct gaze intensify the figure’s physical presence.

The last decade or so of Roberts’s paintings reveals more intense colour, more open pictorial space, less enclosed or silhouetted forms, and more intense handling of the materials. His treatment of his long-standing themes became a kind of metaphor of painting rather than an index of what he painted.

Despite an increased interest in non-representational art in Montréal through the 1950s, Roberts’s authority remains evident in the critical writings of Robert Ayre and Rodolphe de Repentigny, as well as through the respect he has garnered from other artists, including Québec abstractionists like Jean-Paul Riopelle and Paul-Émile Borduas. He was elected to full membership in the Royal Canadian Academy in 1957, and two years later, he became the first artist-in-residence at the University of New Brunswick, with a retrospective at the newly-opened Beaverbrook Art Gallery in 1960. In 1969, he was a recipient of the Order of Canada and was given a travelling retrospective exhibition by the National Gallery of Canada, what was an unusual honour for a living artist at the time. Following his death after a lengthy illness, his work was the subject of several museum solo exhibitions with publications, including a touring retrospective in 1998. Joan Roberts has written a memoir of their life together.

Artistic Technique: Goodridge Roberts is best known for his landscapes of Quebec hills and fields. Using rapid brushstrokes and intense, warm colours, Roberts created a sense of vast space. In figure paintings and still lifes, he used the same loose style, always paying close attention to the relationship of forms. "Must the artist, like the tight-rope walker in a dream-like state of composure, yet always aware of the gulf at his feet, feel both the elation and the uneasiness? One is made forcibly aware of the tension under which one has been working by the sense of relief with which one contemplates a work well done, or of extreme dejection before a badly realized work. There is no truce in this conflict until the brushes are laid down." - Goodridge Roberts,1953