Homer Ransford Watson

Homer Ransford Watson (1855-1936) - Biography

Homer Watson was born into a family of modest means. His father, Ransford, operated a woollen mill. By his own admission, Homer was a poor student who preferred sketching to school lessons. A dreamer too, he was reported to have arranged his food on his dinner plate in such a way as to create images. At age 15 Homer was given some oil paints by an aunt and set about using them. With no money for formal instruction, he learned by copying pictures in books. A small inheritance from his paternal grandfather gave him the means to move to Toronto in 1874 for a year of study. Unable to afford classes, he put up his easel in the foyer of the Normal School. There he copied the reproductions of old-master paintings on display. He also came to know landscapists Henri Perré, Lucius Richard O’Brien, and John Arthur Fraser. In 1876 he was able to spend some months in New York State, where he discovered the Hudson River School of painters. When his funds were exhausted, Watson returned to Doon in 1877 and committed himself to art.

His first major work, The death of Elaine (1877), was inspired by Tennyson’s poem “Lancelot and Elaine.” The work shows the strong influence of the British Romantic School. Elaine would remain one of his few figure studies. The pastoral landscapes in and around Doon – the woodlands, rushing streams, watermills, and grazing cattle – became his predominant subject matter. In the words of curator Darlene Kerr, “Homer Ransford Watson … quite simply loved the woods. It was his sanctum sanctorum, or sacred place.” Watson would later be active in a campaign to conserve an expanse of woodland near his home, known since 1943 as Homer Watson Memorial Park.

In 1878 Watson joined the Ontario Society of Artists (OSA) as a draftsman and designer, and he first exhibited professionally at its annual show that year. The reception from critics was favourable, and shortly afterwards he was elected to the OSA as a painter. More recognition was to follow. In 1880 Governor General Lord Lorne [Campbell*] and his wife, Princess Louise, daughter of Queen Victoria, attended the first exhibition of the Canadian (soon to become Royal Canadian) Academy of Arts (RCA) in Ottawa. So taken was Lorne by Watson’s Pioneer mill that he purchased it for the queen’s collection. The sale, for $300, was the turning point in Watson’s life. The money allowed him to marry his sweetheart, Roxa Bechtel, in 1881. That year Lorne bought a second Watson painting for the queen, The last day of the drought, and the Doon artist’s fame soared. An associate member of the RCA from 1880, he was made a full member in 1882. In 1882, during a visit to Canada, the Irish poet and critic Oscar Wilde viewed an exhibition that included Watson’s work. He was entranced. Pronouncing Watson to be “the Canadian Constable,” a reference to the British landscape painter John Constable, Wilde commissioned a painting for his own collection. The Watsons celebrated these achievements by purchasing the house in Doon (built for Adam Ferrie*, one of the founders of the village) that would become the painter’s permanent gallery.

His success prompted an extended trip with Roxa to the British Isles in 1887–90, the first of a number of visits. Watson was prolific after his return to Canada: he exhibited an estimated 174 paintings between 1890 and 1899, with major shows being held in London and New York. Sales were brisk; among the Canadian collectors who patronized him were prominent businessmen such as James Ross. Generally, his art from this period displays the influence of his years abroad. Some, such as Summer storm (c. 1890) and Evening scene (c. 1894), are darker and moodier than his previous works. Commentators have also pointed to his use of broader brushstrokes and thicker paint, a greater concern with colour and light, and more freedom of expression. The flood gate (c. 1900–1) was the painting that contemporaries, and Watson himself, called his masterpiece. It was exhibited to great acclaim at a show in Glasgow. The painting would be acquired for the National Gallery of Canada in 1925 by director Eric Brown.

The 20th century began auspiciously for him when he won a gold medal at the Pan American Exposition in Buffalo, N.Y., in 1901 (one of several international awards he received over the years). In 1907, along with Edmund Montague Morris*, Albert Curtis Williamson*, and others, he was a founding member of the Canadian Art Club. He served as its first president until 1913, when he was succeeded by his friend Horatio Walker. In 1914 he became vice-president of the RCA, under William Brymner*. After war was declared that August, he was commissioned by the minister of militia and defence, Samuel Hughes*, to paint the camp of the Canadian Expeditionary Force in Valcartier, Que. Watson was elected president of the RCA in 1918, but he withdrew from public life four years later, in part because of increasing deafness.

By 1910 Watson’s work had begun to receive more intense scrutiny as newer talents sought to define the Canadian landscape. Sales of his paintings started to decline. With the formation in 1920 of the Group of Seven, “the Canadian Constable” became an anachronism. The so-called real and raw Canada, as portrayed in the radical canvases of Arthur Lismer*, Alexander Young Jackson*, Lawren Stewart Harris*, and their associates, increasingly dominated the country’s art world. Sensing the shift in the wind, Watson struggled to adapt. His style became more Impressionistic as he sought to work out his own modernism, which did not, he said, “lend itself to the elimination of the pictorial.” Yet most art historians view his paintings from 1920 on as weaker efforts. The stock-market crash of 1929 left Watson virtually penniless. Two years later he transferred ownership of his unsold works to the Waterloo Trust and Savings Company in exchange for monthly living expenses. He continued to paint, but his financial situation remained difficult. Homer Watson died in 1936 at the age of 81, just a month before he was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Western Ontario in London.

Bio c/o The Dictionary of Canadian Biography - Text by Nancy Silcox

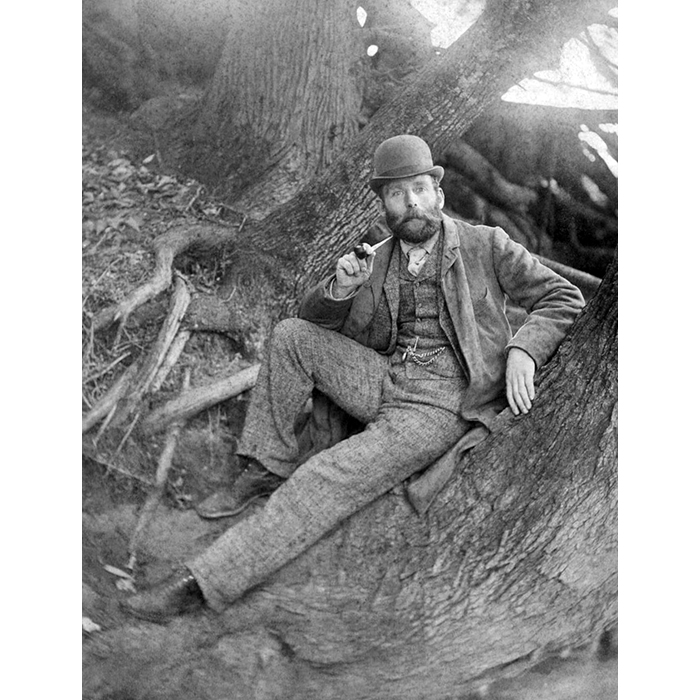

Opposite Photo: Homer Watson, c.1880, photographer unknown, Queen’s University Archives, Kingston. One of the earliest known photographs of Watson.

Awards and Legacy:

On May 27, 2005, Canada Post issued a pair of postage stamps in his honour. Two stamps of denominations 50 and 85 cents were issued depicting two of his works, Dawn in the Laurentides and The Flood Gates. An arterial road in Kitchener, which connects the Doon area to the main parts of the city, is named Homer Watson Boulevard.

Watson has been designated a Person of National Historic Significance in Canada. Watson's former house in Doon, now the Homer Watson House & Gallery, was designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1980.

Permanent Collections:

Art Gallery of Hamilton, ON

Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, NS

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, ON

Art Gallery of Windsor, ON

Beaverbrook Art Gallery, New Brunswick, NS

Canadian War Museum, Ottawa ON

Homer Watson House & Gallery, Kitchener ON

Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery, Kitchener, ON

Mackenzie Art Gallery, Regina SK

Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, QC

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, ON

Royal Collection Trust, Windsor Castle, Berkshire UK

Vancouver Art Gallery, BC

Winnipeg Art Gallery, MB

Artist Specialization: Homer Watson’s earliest work consists largely of Romantic narrative drawings and paintings, often on literary themes. After his early twenties, he devoted himself almost exclusively to landscapes. The overwhelming majority of these depict scenery in and around his hometown of Doon, Ontario, where—except for one extended and six shorter stays in Great Britain, and brief trips to various other parts of Canada as well as the United States and France—he spent his entire life. Watson had a strong interest in nature’s power and drama. This fascination probably derived, at least in part, from woodcuts and engravings in the illustrated books and periodicals, such as the American journal The Aldine, that his family owned when he was a boy. These media often exploit sharp contrasts between dark and light areas of the image, contrasts that seem to be reflected in Watson’s predilection for the dramatic cloud formations associated with stormy weather. Turbulent skies, with their contrasts of light and dark, appear frequently in the early years of Watson’s career, in his sketchbooks and canvases. But above all, Watson’s psychological and emotional attachment to nature was premised on the harmonious relationship between landscapes and humanity.