Mary Pratt

Mary Pratt (1935-2018)

Encouraged from an early age to develop her artistic abilities, Mary Pratt found her expression in drawing and painting. She refined her skills during her studies in the Fine Arts Department at Mount Allison University in Sackville, New Brunswick, graduating in 1961. She studied with the artist Alex Colville, who influenced the development of her style and her subsequent move toward realism. Pratt remarks that childhood memories of light informed her visual vocabulary and influenced her work.

In 1957 Pratt married fellow art student Christopher Pratt, whom she had met at Mount Allison University. By 1964 Pratt had four children and she continued to paint. A combination of events led to a radical shift in Pratt's artistic style. Frustrated by the lack of time she had to devote to art, Pratt began searching for a new working method to describe the heightened modes of perception that were central to her experience. She began to experiment with the use of light to transform an ordinary moment into a charged theatrical scene. What she found, however, was that light changed faster than she could sketch or paint. She responded to the dilemma by using a camera to "still" the light and the moment. The image became a record of a potent visual experience that she could later interpret in her paintings. With this methodology, and with her children older and less demanding of her time, Pratt began working steadily in her studio.

In her work of the 1970s, Pratt addressed the everyday objects of women's domestic lives. By depicting them close-up and in detail, she suggested larger symbolic meaning, as well as a sense of absurdity. Red Currant Jelly (1972) is characteristic of Pratt's elevation of banal domestic activities to the state of ritual. Light plays upon the subject to activate the mundane and infuses it with new meaning. Here jelly is put out to set, but the scene is tenuous and unsettling. The intensity of the late afternoon sunlight reflecting on the liquid becomes suggestive of other red fluids, like wine or blood. This celebration and re-contextualization of the ordinary has earned Pratt a national reputation.

The acclaimed East Coast painter, who was named a Companion of the Order of Canada in 1996, died on August 14, 2018 in St. John’s, Newfoundland, where she lived and worked.

Biography c/o The National Gallery of Canada

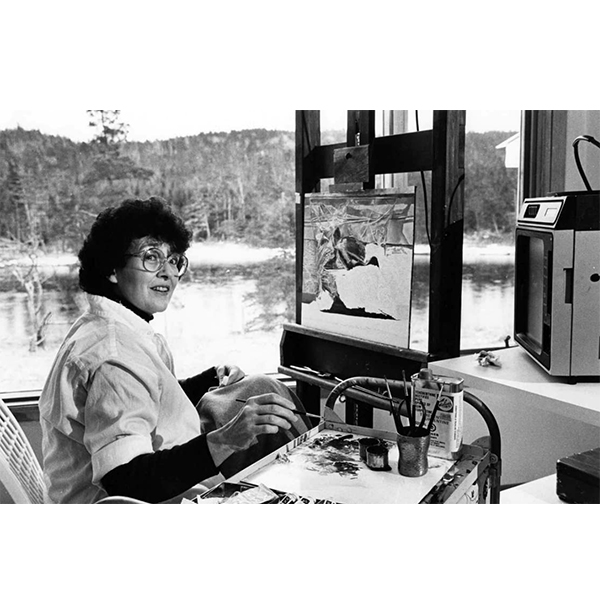

Artist Photo by John Reeves, c/o Art Canada Institute

Major Exhibitions and Public Collections:

Pratt's paintings have been exhibited in most major galleries in Canada, reproduced in magazines such as Saturday Night, Chatelaine, and Canadian Art. Her work is found in many prominent public, corporate, and private collections, including those of the National Gallery of Canada, The Rooms, Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, the New Brunswick Museum, Beaverbrook Art Gallery, Vancouver Art Gallery, Art Gallery of Ontario, and Canada House in England.

Pratt's first solo exhibition was held at the Memorial University Art Gallery in St. John's in 1967. The first showing of her art outside Atlantic Canada was part of an exhibition at the Picture Loan Gallery in 1971 in Toronto. In 1973, Erindale College (Toronto) gave her a show of her own.

The big breakthrough for wider notice of Pratt's work came when the National Gallery of Canada included many of her paintings and drawing in an exhibition in 1975 titled Some Canadian Women Artists curated by Mayo Graham. Her work also coincided with the upsurge of the women's movement (International Women's Year was in 1975 as well). Several colleges and universities began incorporating discussions of her works in their women's studies programs.[6] Public galleries began to show Pratt's work, holding retrospectives, among them Museum London (1981) and the Robert McLaughlin Gallery, Oshawa (1983).

In 1995, the touring exhibition The Art of Mary Pratt: The Substance of Light was organized by the Beaverbrook Art Gallery in Fredericton, New Brunswick. The accompanying catalogue won numerous awards and was included in Great Canadian Books of the Century. Other recent shows at commercial galleries include Inside Light at the Equinox Gallery in Vancouver, Canada (May/June 2011) and New Paintings and Works on Paper at the Mira Godard Gallery in Toronto, Canada (May/June 2012). The exhibition was curated by Tom Smart.

The solo exhibition titled Mary Pratt toured throughout Canada from 2013 to January, 2015. It was organized by The Rooms Provincial Art Gallery and Art Gallery of Nova Scotia and curated by Mireille Eagan, Sarah Fillmore, and Caroline Stone. The accompanying catalogue was published by Goose Lane Editions. The tour traveled to the Art Gallery of Windsor in Windsor, Ontario; the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ontario; the MacKenzie Art Gallery in Regina, Saskatchewan; and the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

The solo exhibition Mary Pratt: This Little Painting was on display at the National Gallery of Canada, running from April 4, 2015, to January 4, 2016. It toured to the Owens Art Gallery at Mount Allison University from March 11 to May 22, 2016. The exhibition was co-organized by the National Gallery of Canada and The Rooms Provincial Art Gallery. It was curated by Jonathan Shaughnessy and Mireille Eagan.

Artist Technique: Mary Pratt's work focused on her relationship with domestic life in rural Newfoundland and common household items: jars of jelly, apples, aluminum foil, brown paper bags. Using photographic projections while painting, Pratt's style was bold and flamboyant, rendering her subject vivid and realistic. Due to this transformation of the mundane into something aesthetic, "she may have had more influence on shaping the way we see things than any Canadian painter since the Group of Seven". Pratt arrived at her signature style in the late 1960s, after discovering that light was her central subject and deciding to incorporate photography into her artistic process. In the early 1990s Pratt and her husband Christopher Pratt separated, which lent her paintings of that period a darker, angry tone. In a 2013 Globe and Mail article, responding to critics of her work as too commercial, she said, "People will find out that in each one of the paintings there is something that ought to disturb them, something upsetting. That is why I painted them."