Pottery & Beadwork

On Talking Earth Pottery

Six Nations of the Grand River in Southern Ontario is the largest reserve community by population in Canada. It is the location for one of Canada’s largest cultural revitalization movements.

During the mid-20th century, artist Elda “Bun” Smith began collecting pottery shards that she found throughout Six Nations. With the assistance of potter Tessa Kidick, Smith and other local potters helped to revitalise pottery on Six Nations. They influenced future generations of artists. Six Nations pottery is now one of the most collected ceramics in Canada. It features in gallery and museum collections around the world.

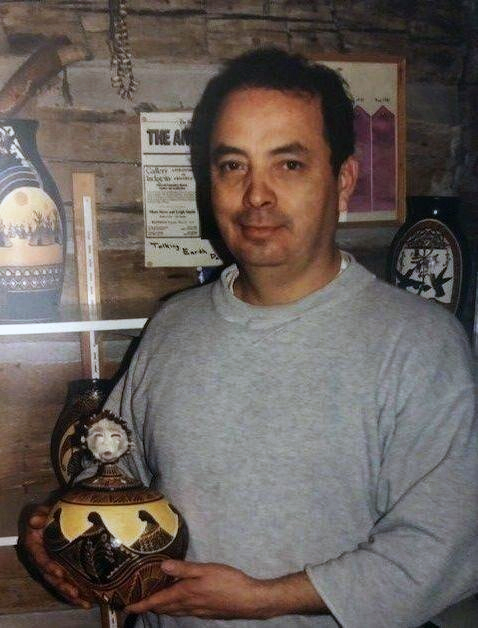

Several pottery studios currently exist on the Six Nations community. They are a result of the efforts of Elda “Bun” Smith and the Mohawk Pottery studio members. For instance, Elda and Oliver Smith passed down their knowledge to their son Steve. He started making pottery at 12 years of age. Steve Smith broke away from the historical tradition. He incorporates studio clay, vibrant colour palettes, dynamic compositions, tribal stories and animated iconography into his work. Like his mother before him, he is now recognized as one of Canada’s most important potters. Steve Smith and his wife, Leigh Smith, operate Talking Earth Pottery studio. They work along with their daughter Santee and granddaughter Semiah. Recently, Santee Smith was commissioned by the Gardiner Museum in Toronto, Ontario. She was commissioned to produce large ceramic pots based on four-cornered Rotinohnsyonni vessels.

Six Nations pottery is now one of the most collectable and sought after art objects from Canada. Their work resides in the collections of the Canadian Museum of History, the National Museum of the American Indian (US) and many others. Its successes are not only felt through individuals and groups in Six Nations. This success is felt throughout the province of Ontario as well as in other Indigenous communities across North America. Through the efforts of the Six Nations potters, other First Nations communities have found inspiration. In particular, the Oneida and Potawatomi have benefitted from these efforts. They have sought guidance in their own endeavours to reclaim previously lost pottery customs.

Photo: Steve Smith